Complex securities in Asia

Complex securities in Asia

Riskier Bets Pitched to Asia’s Rising Rich

Brokers Offer Complex Securities to Growing Affluent Ranks

- Wall Street Journal

By ALISON TUDOR

While U.S. and European investors are favoring safer assets, Asia’s rising wealthy are choosing higher-risk investments. The WSJ’s Alison Tudor tells Deborah Kan why regulators are warning investors they may not understand all the complexities.

In Japan, brokers are dangling what they claim is a tasty product in front of wealthy investors: a “triple-decker” that uses options to squeeze higher returns from stocks, “junk” bonds or other assets.

If a triple-decker doesn’t suit an investor’s fancy, there is the increasingly popular—and slightly less complex—”double-decker.” Elsewhere in Asia, so-called hybrid bonds and other high-yield varieties can be had. Investors in Singapore recently could buy so-called perpetual bonds through ATMs.

Across Asia, brokers are pushing to sell increasingly complex products to the region’s expanding ranks of investors, especially wealthy ones. These types of products appeal to those hungry for yield who normally focus on stocks and real estate but are worried about falling equity markets and the sudden shortage of initial public offerings.

But as the popularity of complex products sold by banks has exploded, some industry observers and regulators are sounding a note of caution.

“The only people who really understand the product and the risk is the small group of product designers, and they don’t fully brief salespeople,” said Satyajit Das, a former banker and author of books on risk in the global financial system and the use of derivatives.

Bankers increasingly are relying on well-off Asians to soak up demand for their high-yield products. The number of wealthy Asians with at least $1 million to invest rose by 1.4% to 3.37 million in 2011, outnumbering peers in North America for the first time, according to a report Wednesday by Capgemini and Royal Bank of Canada.

Asian private banking clients are typically younger than in Europe and the U.S., take more risks and trade more frequently, according to consultants and bankers.

Regulators in Singapore, Japan and Australia have weighed in on some of the products. One example is perpetual bonds, which offer higher yields than typical bonds but are risky because the principal may never be repaid and interest can be deferred.

Overall, companies have sold $5.16 billion of these hybrid securities in the Asian-Pacific region so far this year, according to Dealogic. That is a record compared with the same period in previous years, when this form of debt was rare in the region.

Casino operator Genting Singapore PLC sold a $390 million perpetual bond in April that bank customers could buy at ATMs with the press of a few buttons. Its attraction was a yield of 5.125% at a time when the yield on 10-year U.S. Treasurys was 1.62%, near record lows.

After that sale, the Monetary Authority of Singapore told a local newspaper that it expects issuers to make clear to investors the difference between perpetual securities and other bonds. The authority declined to comment about its conversations with bankers on the subject and referred to the article.

More

In Australia, Peter Kell, commissioner of the Australian Securities and Investments Commission, has said some brokers are making margins of 1.75%—relatively high, say analysts—to push hybrid bonds, which include characteristics of stocks, to retail investors who don’t understand the potential risks.

“There’s considerable anecdotal evidence that these products are being pushed in a way that highlights the well-recognized [corporate] names without the risk,” Mr. Kell said.

In recent months, Australian household names, including Westpac Banking Corp. WBC.AU +0.43%and Woolworths Ltd., WOW.AU 0.00%have issued subordinated debt, which usually offers higher yields but ranks lower in priority if a company goes bankrupt.

Mikey Burton for The Wall Street JournalLet Them Eat Cake: How a ‘triple decker’ works

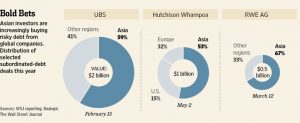

Asian investors have become increasingly important sources of capital globally as U.S. and European investors scale back. Asia-based investors, particularly private-bank clients, bought 60% of Swiss bank UBS AG’s UBS -0.27%subordinated debt in February, 53% of Hong Kong’s Hutchison Whampoa Ltd.’s 0013.HK -1.12%in May and two-thirds of German RWE AG’s in March.

Bankers are predicting robust demand for these products going forward.

“We expect to see a lot more hybrid issues in Hong Kong and Singapore,” said Fritz Man, head of investment products Asia, Bank Sarasin & Cie AG, Hong Kong Branch.

The history of complex products in Asia isn’t pretty. In 2008, thousands in Hong Kong invested 20.23 billion Hong Kong dollars (US$2.6 billion) in securities linked to Lehman Brothers Holdings Inc. only to see their value wiped out when the Wall Street firm collapsed. These so-called minibonds also were sold in Taiwan and Singapore.

Noisy demonstrations outside the banks continued for years, with 20,000 investors complaining to Hong Kong regulators that they had bought the bonds without knowing all the risks. The banks that sold the bonds agreed in 2009 to compensate the majority of investors’ money, while legislators have called for a shake-up of regulators’ jurisdictions and suggested barring some investors from buying structured products.

Some foreign asset managers say they are looking to Japan for inspiration for more extreme products. Two decades of ultralow interest rates has prompted a flurry of innovation to cater to the country’s aging population.

One popular product has been the double-decker, which includes investments in an underlying asset such as high-yield bonds along with a high-yield currency such as the Brazilian real. A popular attribute of the double-decker among Japanese pensioners who typically buy them is their monthly dividend. From almost no market at the end of 2008, double-decker funds rose to $105 billion at the end of March. Such funds with monthly dividends also are becoming popular in South Korea and Taiwan, say consultants.

Japan’s financial watchdog, the Financial Services Agency, tightened the guidelines on selling risky products to inexperienced investors earlier this year. But that isn’t stopping even more complex products from entering the market.

A recent innovation is the triple-decker, which adds another layer of complexity by using derivatives to juice returns. Examples of multilayered products are Rakuten Investment Management’s U.S. REIT Triple-Engine and Daiwa Asset Management Co.’s U.S. Stock Strategy Alpha Triple Returns.

ITC Investment Partners’ Japan Stock High Income fund is sold to retail investors by online Japanese brokers that display the prospectus on websites. A representative at ITC said the fund yields on average double-digit dividends.

Rakuten, ITC and Daiwa say they comply with the regulator’s new guidelines.

Some of these products are structured so that if currencies unexpectedly change direction, or the bond issuer fails to make payments, it can quickly result in the investor losing money.

“Regulators are right to say this is a market in which bad things can happen to people who are inadvertently leveraged or leveraged in ways that they didn’t understand,” said Charles Beazley, chairman and chief executive of Japan’s Nikko Asset Management Co., the largest regional asset management company headquartered in Asia-Pacific in terms of assets under management and distributor networks.

He said Nikko Asset Management does sell double-deckers but drew the line at triple-deckers, adding that he had not been asked by his distributors to provide the product either. Nikko Asset Management set up an in-house academy in 2008 for its distributors, from state-owned Japan Post Holdings Co. to brokerage SMBC Nikko Securities Inc., whose salesmen spend on average a day-and-a-half learning about products.